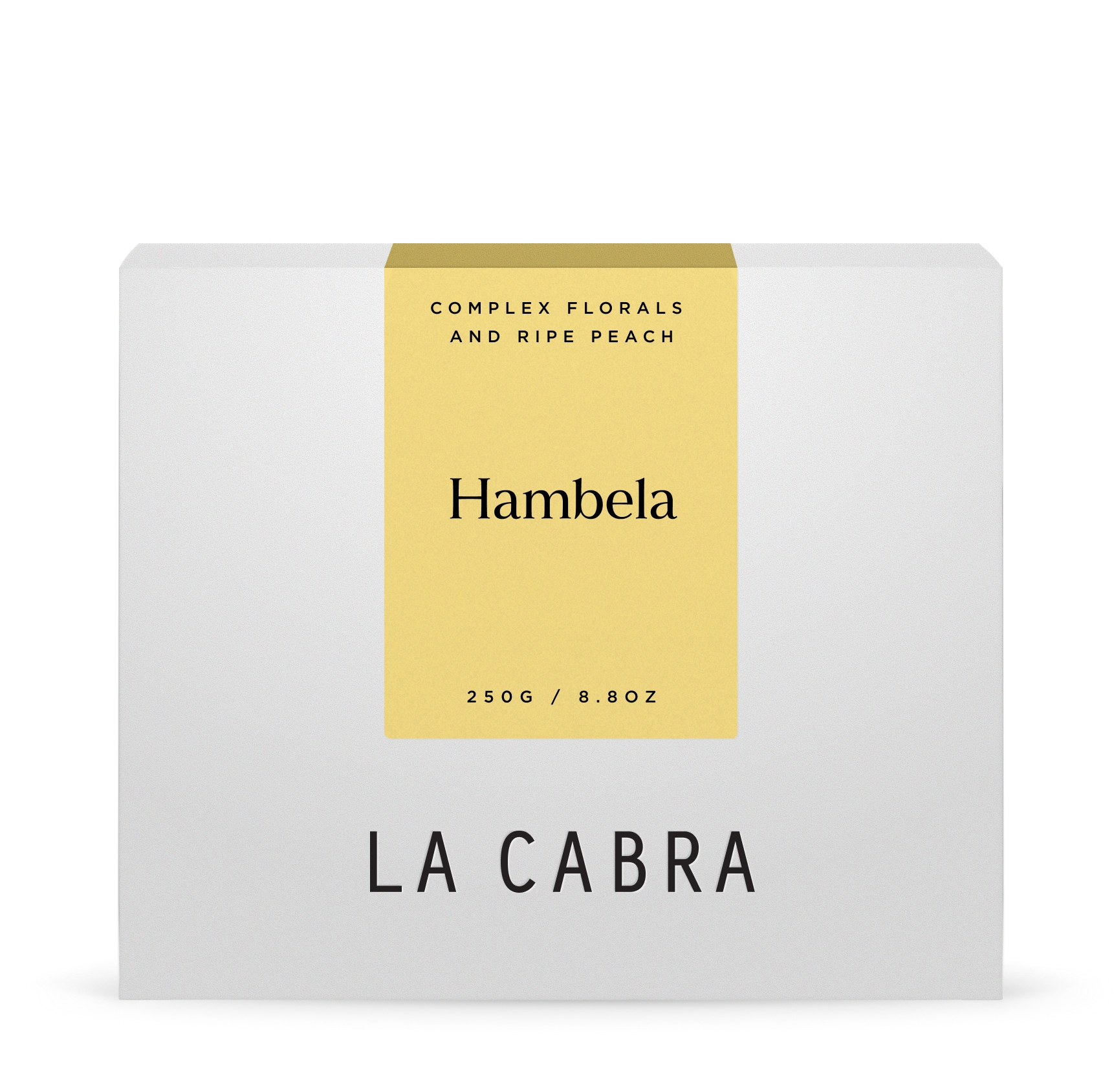

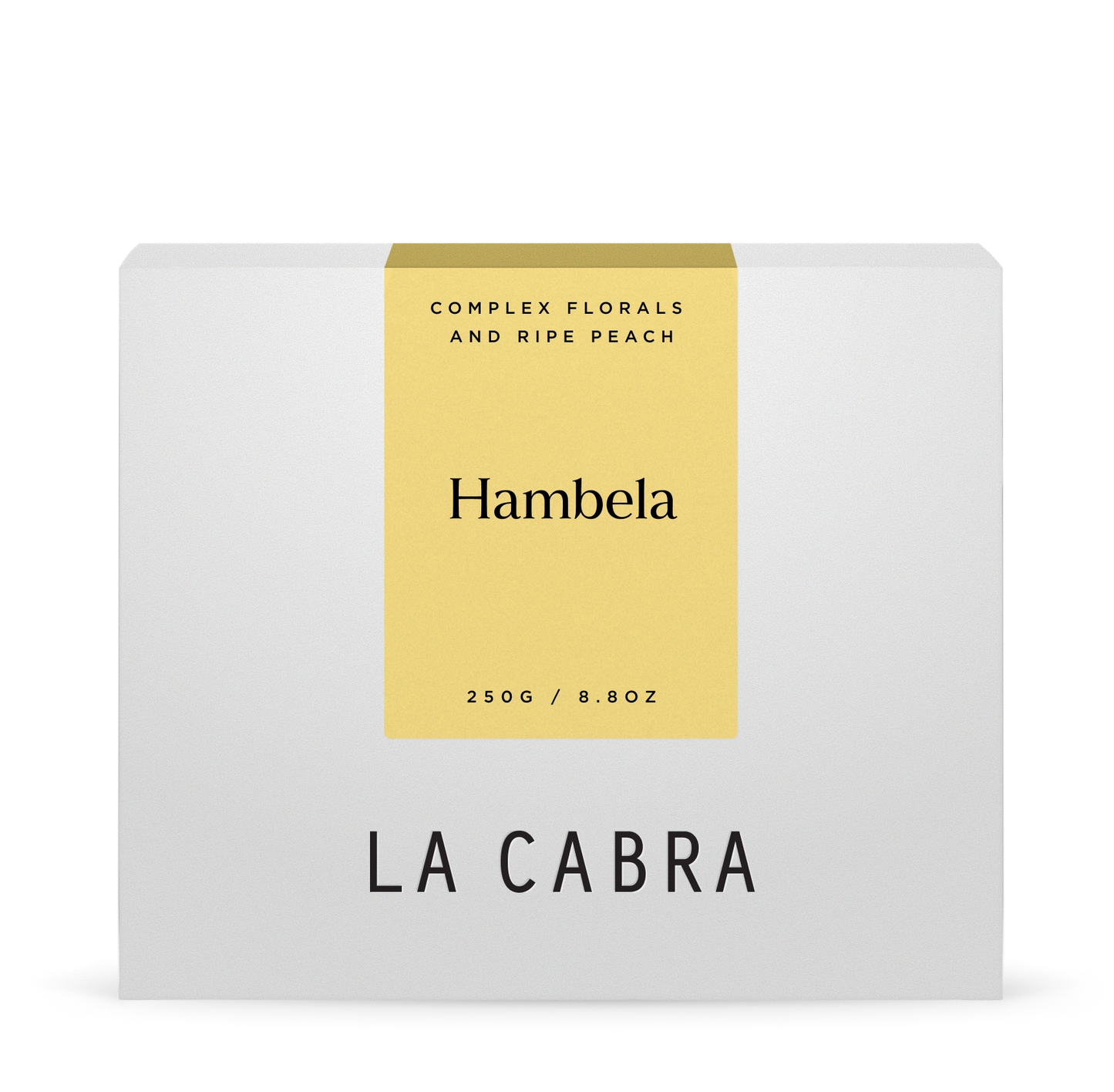

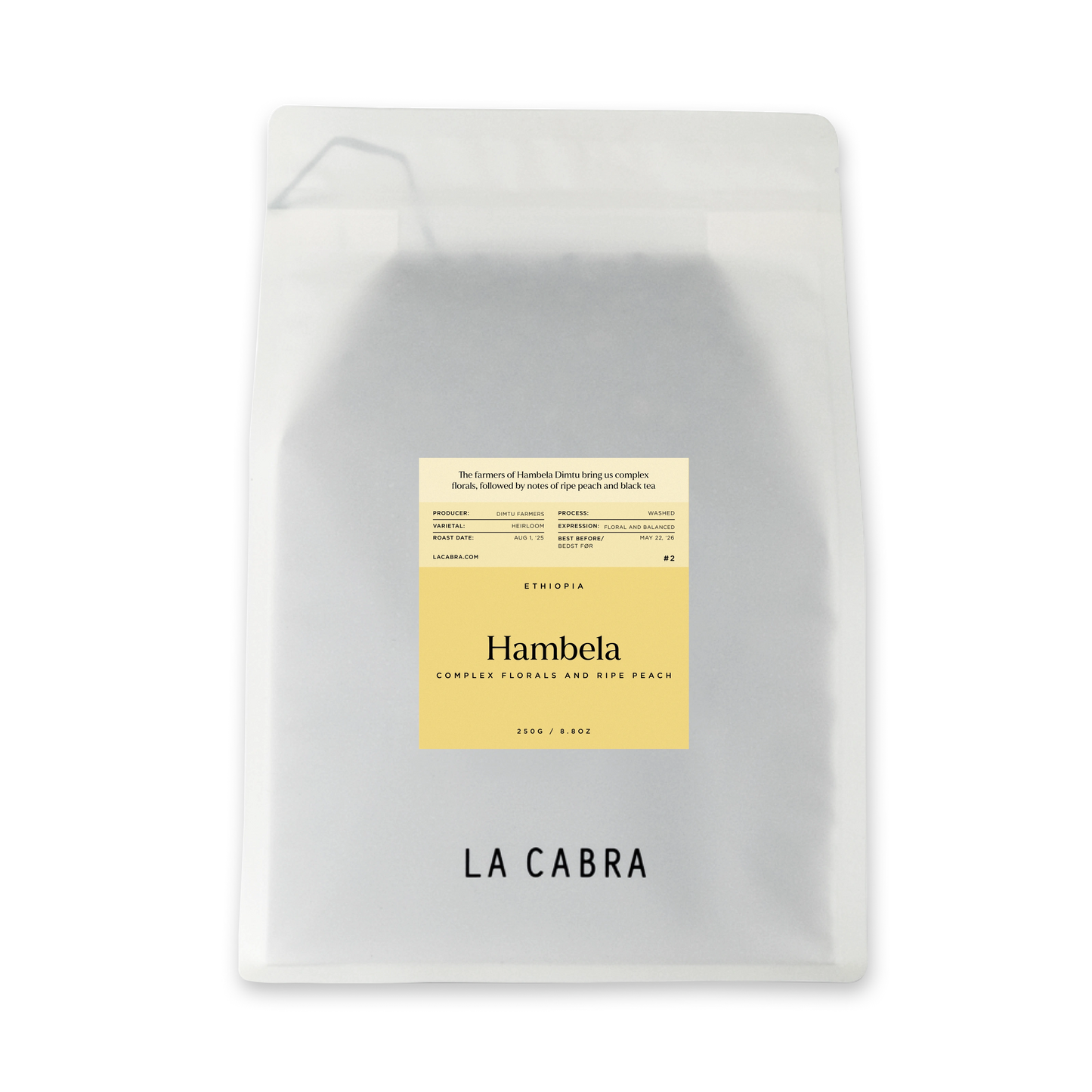

Hambela Dimtu

The Dimtu station is located in the village of the same name, in the Hambela sub region of Guji. The station collects cherries from smoe of the highest altitude farmers in the region, from 2100 to 2300 masl, leading to excellent potential for quality. This is realised at one of the most technically advanced stations in the region; the team in Dimtu use advanced eco-pulping equipment to reduce water usage and create more control over the cup, especially in their washed coffees.

-v1757660067511.jpg?1200x800)

In order to ensure quality, the team at the station pay close attention to cherry selection and sorting.

Coffees are floated upon arrival to remove low density underripe or defective fruit, and then constantly sorted throughout process, in washing channels and on the beds. This leads to a very low level of defects and a high degree of uniformity in the final lot, vital in ensuring quality in combined smallholder lots. This lot in particular has complex floral aromas, ripe peach notes, and a black tea finish, with the heavier body typical of Guji.

-v1757660068726.jpg?900x1125)

-v1757660072543.jpg?900x1125)

-v1757660074583.jpg?900x1125)

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, coffee still grows semi-wild, and in some cases completely wild. Apart from some regions of neighbouring South Sudan, Ethiopia is the only country in which coffee is found growing in this way, due to its status as the genetic birthplace of arabica coffee. This means in many regions, small producers still harvest cherries from wild coffee trees growing in high altitude humid forests, especially around Ethiopia’s famous Great Rift Valley.

-v1757660070251.jpg?1200x800)

Forest coffee makes up a great deal of Ethiopia’s yearly output, so this is a hugely important method of production, and part of what makes Ethiopian coffee so unique. Deforestation is threatening many of coffee’s iconic homes in Ethiopia, leading to dwindling yields and loss of biodiversity; significant price fluctuations over the past decade have led many farmers to replace coffee with fast growing eucalyptus, an incredibly demanding crop in terms of both water and nutrient usage.

Throughout these endemic systems, a much higher level of biodiversity is maintained than in modern coffee production in much of the rest of the world. This is partly due to the forest system, and partly down to the genetic diversity of the coffee plants themselves. There are thousands of ‘heirloom’ varieties growing in Ethiopia; all descended from wild cross pollination between species derived from the original Arabica trees. This biodiversity leads to hardier coffee plants, which don’t need to be artificially fertilised.

This means that 95% of coffee production in Ethiopia is organic, although most small farmers and mills can’t afford to pay for certification, so can’t label their coffee as such. The absence of monoculture in the Ethiopian coffee lands also means plants are much less susceptible to the decimating effects of diseases such as leaf rust that have ripped through other producing countries. Maintaining these systems is important, both within the context of the coffee industry, and for wider biodiversity and sustainability.

-v1757660076153.jpg?900x1125)