-v1721371604053.jpg?1200x800)

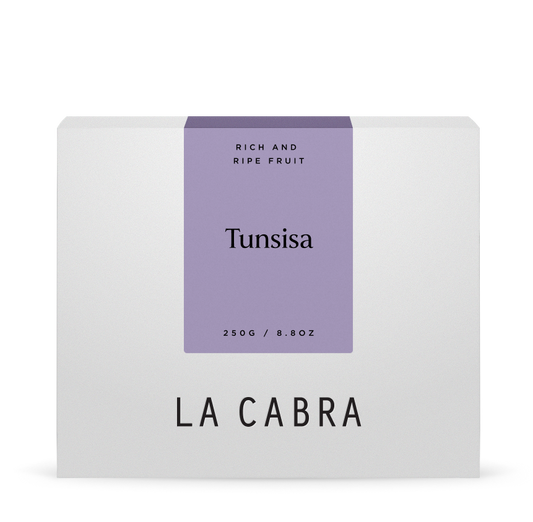

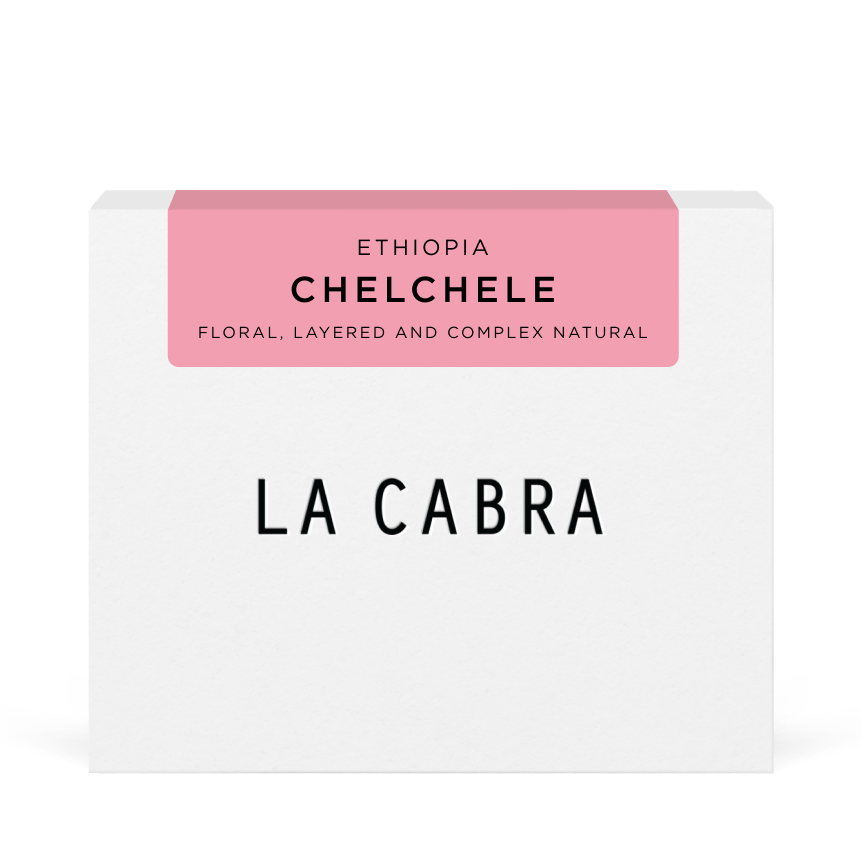

Our first Ethiopian release of the year is from the Chelchele station in Yirgacheffe; citrus aromatics and complex fruit

Chelchele

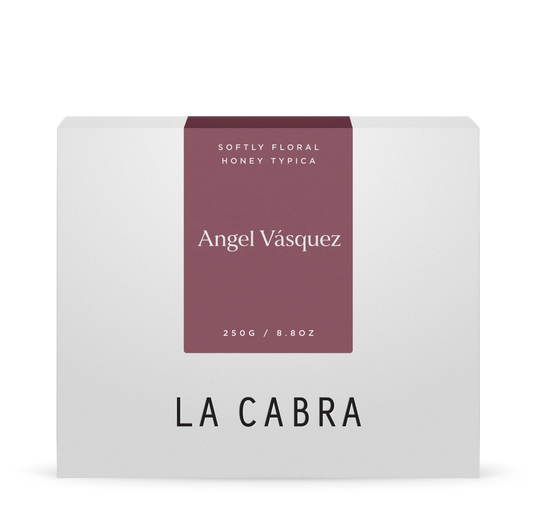

Chelchele was produced at a station owned by EDN Coffee in the village of Layo Genet, in Gedeb. The cherries for this specific lot come from farmers in the village of Banko Chelchele, in the same zone, in the high altitudes of Southern Ethiopia, between 1900 and 2300 metres above sea level in the centre of the area that produces ‘Yirgacheffe’ coffee.

-v1721371600097.jpg?1200x800)

-v1721371605532.jpg?1200x800)

Yirgacheffe

In Yirgacheffe, coffee farming is a way of life deeply ingrained in the community's heritage. Passed down through generations, the people here have amassed a great deal of knowledge and expertise within cultivating and harvesting coffee. This rich cultural connection to coffee has shaped the community's traditions and livelihoods, making it an integral part of their identity. Harvest here takes place between October and December, where farmers begin to handpick cherries before delivering them to one of the local stations.

-v1721371601766.jpg?900x1125)

Here at EDN’s station Chelchele, natural coffees are dried in the sun. This can take up to 2-4 weeks, turned regularly to ensure even and controlled drying.

This leads to a deep and layered complexity in the cup, with elements of berry and stone fruit backing up citrus and floral aromatics. An excellent start to our Ethiopian season.

-v1721371607529.jpg?900x1125)

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, coffee still grows semi-wild, and in some cases completely wild. Apart from some regions of neighbouring South Sudan, Ethiopia is the only country in which coffee is found growing in this way, due to its status as the genetic birthplace of arabica coffee. This means in many regions, small producers still harvest cherries from wild coffee trees growing in high altitude humid forests, especially around Ethiopia’s famous Great Rift Valley.

-v1721375778511.jpg?900x1125)

There are three categories of forest coffee growing in Ethiopia, Forest Coffee (FC), Semi-Forest Coffee (SFC), and Forest Garden Coffee (FGC), with each having an increasing amount of intervention from coffee producers. Forest coffee makes up a great deal of Ethiopia’s yearly output, so this is a hugely important method of production, and part of what makes Ethiopian coffee so unique.

Deforestation is threatening many of coffee’s iconic homes in Ethiopia, leading to dwindling yields and loss of biodiversity; significant price fluctuations over the past decade have led many farmers to replace coffee with fast growing eucalyptus, an incredibly demanding crop in terms of both water and nutrient usage.

-v1721375654795.jpg?900x1125)

Throughout these endemic systems, a much higher level of biodiversity is maintained than in modern coffee production in most of the rest of the world. This is partly due to the forest system, and partly down to the genetic diversity of the coffee plants themselves. There are thousands of so far uncategorised ‘heirloom’ varieties growing in Ethiopia; all descended from wild cross pollination between species derived from the original Arabica trees. This biodiversity leads to hardier coffee plants, which don’t need to be artificially fertilised. This means that 95% of coffee production in Ethiopia is organic, although most small farmers and mills can’t afford to pay for certification, so can’t label their coffee as such.

The absence of monoculture in the Ethiopian coffee lands also means plants are much less susceptible to the decimating effects of diseases such as leaf rust that have ripped through other producing countries. Maintaining these systems is important, both within the context of the coffee industry, and for wider biodiversity and sustainability. Our primary partners in Ethiopia, Moplaco, have made it their mission to inform of this destruction, and to continue supporting the communities they work in in order to make coffee a profitable and attractive business.

-v1721375756900.jpg?900x1125)